Sandwich Manufacturing Co. History

The Sandwich Manufacturing Co.

was started in 1856 when Augustus Adams moved from Elgin, Illinois where he had

been active in the foundry business. Adams and his 2 older sons developed

their own brand of spring and cylinder corn shellers, both hand and power

operated, and soon branched out into other types of farm equipment. While

not as large as many of the other equipment manufacturers, the Sandwich Line of

high quality equipment was known the world over.

As the demand for engine power

to run their machines developed, the company began to handle other company's

engines. Notable was the Chanticleer engine of Jacob Haish of DeKalb,

Illinois which was brought out in 1904. Haish's factory burned in 1912,

and Sandwich contracted with Stover of Freeport, Illinois for engines while

developing their own line of engines. Several of the engineers were former

Haish employees, which explains the resemblance between the two brands of

engines.

With a large foundry and

machine shop, Sandwich was able to market their first "Excess Power" engines in

1913. These were a well designed, high quality engine rated well below

their actual horsepower output. Available were 1 1/2, 2 1/2, 4, 6, 8, and

10 hp engines. If sold by another company, the 1 1/2 hp engine would have

been rated at least a 2 hp or maybe a 2 1/2 hp and in some cases as high as a

3hp engine. In the middle 1920's, the smaller engines were re-rated from 1

1/2 hp to 2 hp, 2 1/2 hp to a 3 hp, 4 hp to 4 1/2hp, and the Light 6 was

introduced. This was basically a 4 hp engine with some minor

modifications. Also introduced were the 1 1/4 hp Cub and the 1 1/2 hp

Junior. On these, the base and cylinder were one piece rather than the 2

piece common to the rest of the line.

Sandwich Manufacturing Co. was

sold to New Idea Spreader Co. of Coldwater, Ohio in 1930, and the manufacture of

Sandwich Engines were stopped. New Idea soon developed their own

Vari-Speed 1 1/2 - 2 1/2 hp throttle-governed engine with a closed

crankcase. These were built in Sandwich, Illinois from 1930 to about

1935. With demand for small engines of this type falling off, New Idea

dropped them from the catalog, but still sold parts for Sandwich & New

Idea engines into the 1940's.

As New Idea began to

consolidate their product line, the plant at Sandwich was converted to a

warehouse and Dealers Training Center. As part of the change over, all of

the old Sandwich and later New Idea records were destroyed along with over 100

tons of parts for everything from hand shellers to engines. All Engine

records were burned during the clean-up.

History from Ray

Forrer

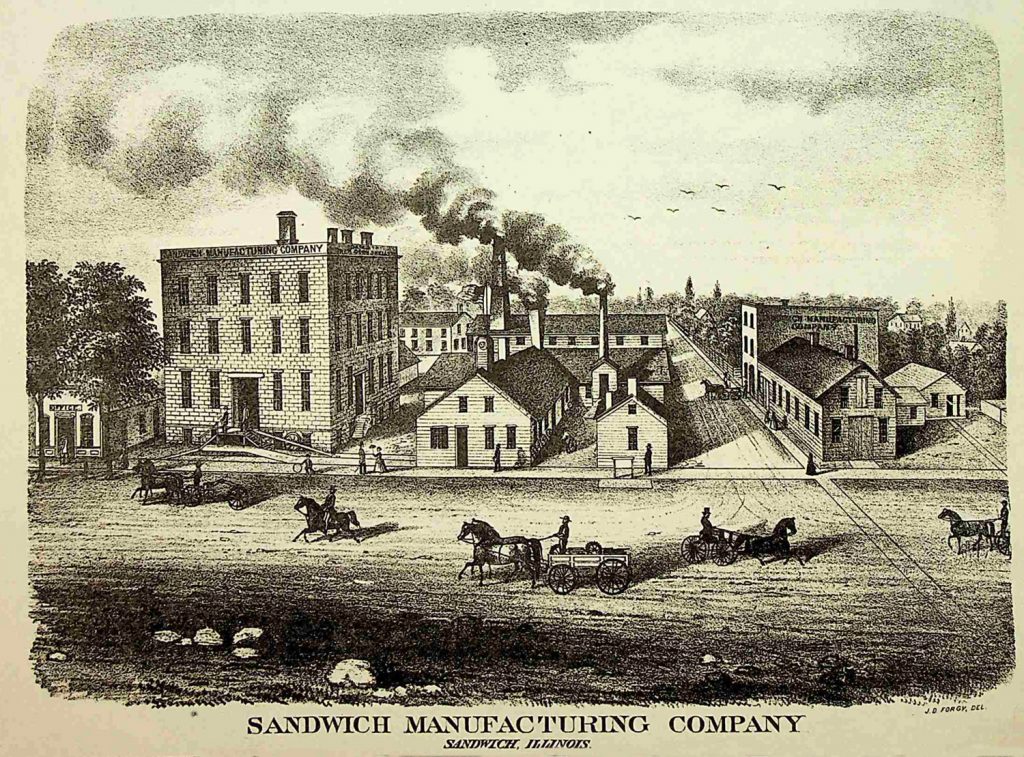

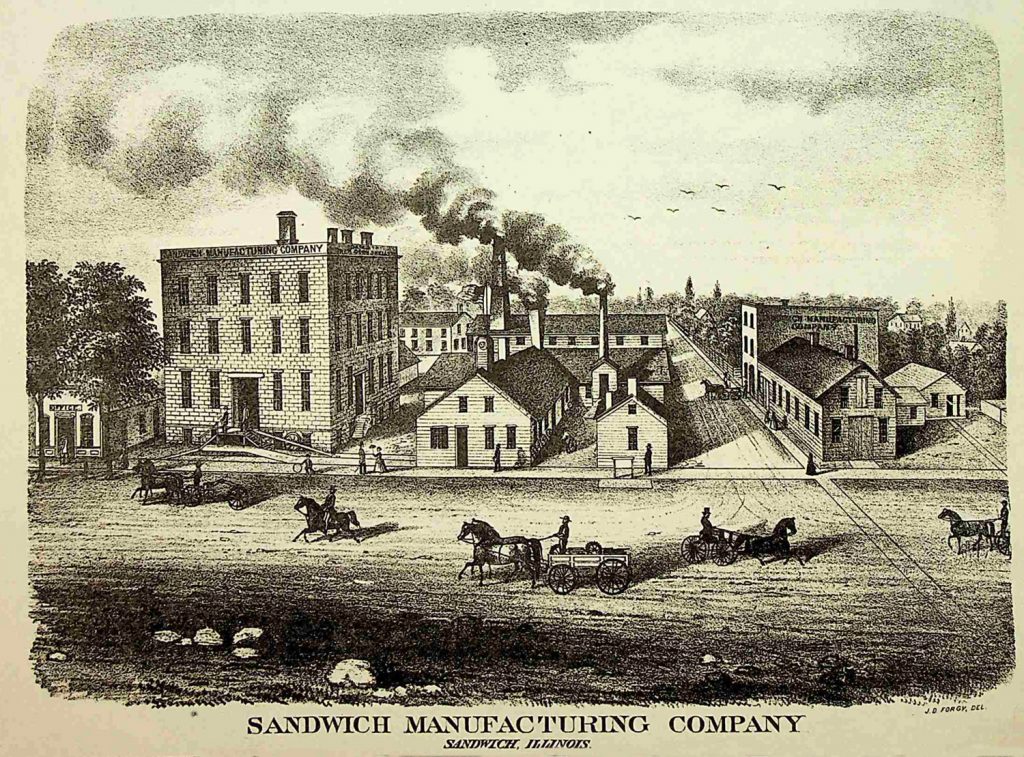

The Sandwich

Manufacturing Company of Sandwich, Illinois

by Brian Wayne Wells

(This article was published in the July/August 1998 issue of Belt Pulley

magazine.)

Farm

equipment companies that did not sell a “full-line” of farm equipment they were referred to as “short line”

companies. Usually these short line companies did not produce farm

tractors and most often did not even produce stationary engines.

Inevitably, these small companies were swallowed up by larger companies and, in

the process, the individual identity of these small companies was lost.

Often, however, many of the greatest improvements in farm machinery were made by

these short line companies. One of the most inventive and creative of all

short line companies was the Sandwich Manufacturing Company of

Sandwich, Illinois.

The

Sandwich Company began as a concept in the mind of one person–Augustus

Adams. Augustus Adams was born in Genoa, New York, on May 10, 1806.

Genoa is located in the “Finger Lakes” Region of New York near Syracuse.

Today, the town is known as the birthplace of Millard Fillmore (1800-1874), who

was later to become the thirteenth President of the United States.

Following the death of his father, Samuel Adams, in 1817 (not the

famous hero of the American Revolution), Augustus was sent to live with his

brother-in-law in Chester, Ohio. There, he alternated between attending

school and doing farm work in the area. He was studious by nature and

devoted a great deal of his leisure time to studying and reading. In 1829,

he returned to the Finger Lakes Region and settled in Pine Valley located in

Chemung County near Elmira, New York. In Pine Valley he opened a foundry

and machine shop, which he operated until 1837 when he was smitten by the dream

of seeking his fortune in the west.

A

generation before John Babsone Lane Soule pronounced his famous quote of “Go

West, young man” in the Terre Haute Indiana Express in 1851 (later

popularized by Horace Greeley), the dream of seeking riches on the Western

frontier was firing the imaginations of many young people. (John Bartlett,

Familiar Quotations [Boston 1968], p. 768.) So it was with young

Augustus Adams. Augustus had married Lydia A. Phelps on October 21, 1833,

and started their family. Over the next few years they had four sons:

Darius (August 26, 1834); J. Phelps (September 18, 1835); Henry A. (January 21,

1837); and John Q. (July 23, 1839). However, Augustus was extremely

reluctantly to take his family to the untamed western frontier, and so he left

them in New York while he struck out for the town of Elgin, located in northern

Illinois, northwest of Chicago. He intended that the family would follow

as soon as he could make decent living arrangements for them on the frontier in

Illinois.

Augustus,

who from his own experiences in working on a farm, knew that much hard,

laborious hand work was involved in raising and harvesting crops.

Consequently, he understood that the future of any business would be assured if

the business could build labor-saving farm equipment, and over the next several

decades, the company that Augustus Adams founded would do just that.

At first,

Adams set out building a “grain harvester” which cut the grain and collected it

on a platform to be bound. Of course, Cyrus McCormick had already built

the first machine for cutting grain on the McCormick farm in the Shenandoah

Valley of Virginia in 1831, but Virginia was a long way from Northern Illinois

in the 1830s. Besides, Augustus had several refinements that he wished to

see incorporated into the grain cutting machine that were not part of the

McCormick machine. If he could manufacture his machine in substantial

quantities, Augustus would have the entire local market for these machines

completely to himself. By the fall of 1838, Augustus’ original grain

harvester was in operation. That same fall, Augustus established a foundry

and machine shop in Elgin to build duplicates of the harvester to sell to area

farmers.

In the

fall of 1840, Augustus was finally able to bring his wife and four sons to join

him in Elgin, Illinois. Soon their family grew to include five more

children: H. Raymond (June 29, 1842); Amy W. (May 29, 1844); Oliver R.

(September 10, 1845); Walter G. (July 12, 1848); and Charles H. (February 17,

1855).

In 1841,

Augustus took on a partner in his business venture: James T.

Gifford. Theirs was a small operation, but it was marked by a

generous spirit. Once Augustus needed a small amount of hard coal for

experimentation purposes, so he ordered a couple hundred pounds from a

commission house in Chicago. Two months later, he received word that his

coal had arrived in Chicago, but the amount that had actually been sent was a

full ton. The commission house was put in a difficult spot because it had

no immediate prospect of selling the coal. However, Augustus Adams

good-naturedly agreed to help the commission house out by purchasing the full

ton of coal.

Over the

years, Augustus continued to work on improvements to the grain harvester.

One such improvement was developed by Augustus in partnership with another

inventor, Philo Sylla. This was the “hinged sickle bar.” The hinge

at the base of the sickle bar allowed the sickle bar to be held in an upright

position for transport. This was the first time that such a hinge had been

used on a mower. The hinged sickle bar has remained a standard part of

sickle bar mowers down to the present day.

In 1856,

Augustus moved his company from Elgin to Sandwich, Illinois, 35 miles to the

southwest. There, he and his oldest sons–Daius, J. Phelps and

Henry–established a new machine shop under the name of A. Adams &

Sons. Augustus became the president of the company; his second son,

J. Phelps, became secretary; and his third son, Henry A., became

treasurer. One of the major benefits of moving to Sandwich was that the

town was served by the newly completed Chicago Burlington and Quincy

Railroad or C.B. and Q. line running east and west through the

town. It was now possible for rail traffic to run uninterrupted from

Chicago, through the town of Sandwich, and on to the Mississippi River town of

Burlington, Iowa. (Robert P. Howard, Illinois: A History of the

Prairie State [Eerdmans Publishing: Grand Rapids, Mich. 1972], p.

247.) Consequently, products produced by A. Adams and Sons would

most assuredly reach nearly every major point in the midwest by direct

connection with the C.B. and Q. railway.

Because

corn was already replacing wheat as the leading farm crop in Illinois, it was

natural that a great many machine shops in Illinois began manufacturing machines

which would aid in processing corn. The A. Adams and Sons machine

shop was no exception. Because shelled corn was easier to store and

transport, due to the reduced amount of space needed for shelled corn in a sack

as opposed to ear corn, corn shelling machines were in great demand by

farmers. Thus, in 1856, A.Adams and Sons began experimenting with

a “power corn sheller” in 1856. The first Adams sheller was

powered by a small steam engine. By 1857, the power corn sheller was in

operation, having been improved by the addition of a larger steam engine which

could keep the corn sheller working at optimum speed. This larger steam

engine was easier to obtain in quantity, and so better suited to Adams’ purposes

when A.Adams and Sons began to mass produce the corn sheller.

Over the

years, Augustus patented several of his ideas for improvements to the corn

sheller; including a multiple spring-type sheller, employing steel rods in the

cage of a cylinder sheller, using an adjustable limit stop on the rasp bar of

the sheller, providing a flat rim flywheel for the belt drive, providing open

driving teeth on the feeder wheel to prevent crushing of kernels, and utilizing

offset teeth on the feeder wheel to provide easy entry of the ears. Adams’

most important innovation, however, was the “self feeder” for the corn sheller

which was invented in 1860. The self feeder was the same type of chain,

drag-line self feeder that is used on modern corn shellers designed for shelling

corn from corn cribs. The power self feeding corn sheller marketed by

Adams and Gifford became a very popular item.

At about

the same time, Adams’ shop also started making mechanical hay presses,

forerunners of the modern hay baler. The stationary hay press was most

often powered by horses harnessed to a revolving device called a “sweep,” where

the horses walked around in circles and generated power which was transferred to

the hay press by belt. The hay press also became a popular mass-produced

item sold by the Adams’ shop. By 1861, the Adams machine shop was

employing a large force of men in the manufacture of corn shellers and hay

presses.

In 1861,

fire destroyed the machine shop. However, Augustus took advantage of this

loss to expand his business by building newer, larger facilities. On April

15, 1867, the Adams firm was incorporated as the Sandwich Manufacturing

Company.

Personal

loss, however, tempered the joy of starting a new enterprise in the new

location, as Augustus’ wife Lydia died on December 14, 1867. On January

13, 1869, Augustus Adams would marry Mrs. L.M. Mosher. In 1870, Augustus

established his younger sons in a new Sandwich Company-owned facility

in Marseilles, Illinois. The town of Marseilles was chosen because of the

water available at that location which promised to be a cheaper source of power

than the steam power used at Sandwich. The new corporate entity, known as

the Marseilles Manufacturing Company, was organized to handle the

manufacture of the corn sheller, while the Sandwich Company itself

concentrated on the manufacture of the hay press. In 1873, Augustus Adams

resigned from his position as president of the Sandwich Manufacturing

Company and left the running of that company to his older sons while he

went to Marseilles to join his younger sons and to become president of the

Marseilles Manufacturing Company.

The older

Adams sons, now in total charge of the Sandwich Company, entered into a

joint venture with William Low and T.L. French for the production of grain

binders in Cedar Falls, Iowa. The joint venture first was called the

Low, Adams and French Harvester Company. It later became the

Adams and French Harvester Company. The first models of grain

binders the partnership produced were hand binders; however, they were pioneers

in the development of the wire self-tying grain binder. All the grain

binders sold by the Cedar Falls-based venture were manufactured at the

facilities of the Sandwich Company. Later, the Sandwich

Company bought out the other partners and became the sole owner of the

binder manufacturing operation.

In 1883,

the Sandwich Company was struck by another devastating fire which

destroyed all of its factory buildings in Sandwich, Illinois. Once again,

the company had to rebuild its factory from scratch, and once again, the company

took the opportunity to expand their facilities as it rebuilt the

factory.

As a

natural consequence of being involved in the manufacture of the hay press, the

Sandwich Company turned its inventiveness to other machines to ease the

labor involved in hay-making on the average farm. One particular

hay-making machine was soon to become one of the Sandwich Company’s

best sales items. This was the hay loader.

An

Iowa inventor had created a sensation among farmers in 1890 by his successful

demonstration of a hay loader which followed a wagon and incorporated a raking

cylinder pickup to lift hay automatically from the ground to the wagon.

The Sandwich corporate leadership quickly saw the possibilities of this

hay loader and, in 1891, contracted with the inventor to obtain exclusive rights

to manufacture this hay loader under its name. The Sandwich

Company started producing two separate models of their hay loader–”Old

Reliable” (later named “Clean Sweep”) and the “Easy Way.” The Sandwich

Company made several improvements to the original design of the hay loader,

most important of which was the creation of the push-bar elevator. Soon

hay loaders of similar designs were being manufactured by many different

companies and being sold by the thousands. However, hay loaders, of

whatever manufacture, always retained the same basic design as had been

incorporated in the original Sandwich design.

Although

advertisements for the “Clean Sweep” hay loader indicated that the hay loader

would work well on hay either in a swathe or a narrow windrow, clearly the Clean

Sweep, like all hay loaders, would work better when the hay had been raked into

a windrow. For one thing, the horses pulling the wagon and hay loader

could walk on either side of a narrow windrow and not have to tread on the new

hay. Furthermore, because the windrow was narrow, the whole width of the

pickup cylinder on the hay loader was used. Consequently, turning the

corner of a windrow could be accomplished much easier, with less hay being left

on the ground. Answering the need for a windrowing device, the

Sandwich Company pioneered the development of the side-delivery hay

rake whose basic design would remain unchanged to this day. Indeed, with

the advent of the mechanical hay loader and the side-delivery rake to the farm,

the dump rake and hand-loading with a pitch fork would be replaced within a very

short period of time. Furthermore, the pattern of hay making was

established and would remain unchanged for the next 60 years. The

Sandwich Company had a great deal of influence on this

process.

In 1894,

the Sandwich Company designed and built a portable grain elevator

intended for use on the typical family farm. Several years later, after

finalizing refinements to the basic design, the portable grain elevator was mass

produced for sale to the public. Here, too, a number of innovations were

made to the elevator and wagon unloading: including a safety screw-type raising

and lowering device for the wagon dump; use of steel troughs stiffened by double

truss rods; reinforcing the steel metal troughs with box crimps; employing steel

rather than malleable chain; and making the carrying truck adjustable to

accommodate elevators of various lengths.

Additionally, some time before 1908, the Sandwich Company began

production of several different models of its own internal combustion “hit and

miss” stationary engines. Among these engines were the 1-1/2 hp. “Cub;”

the 1-3/4 hp. “Junior;” the 2-1/2 hp. Model T; and a 4 hp. engine.

Sandwich also offered two different models of a 6 hp. engine, an 8 hp.

engine, and a 10 hp. engine. These engines were sold separately, or as

sources of efficient power for hammer mills, portable grain elevators, and other

equipment in the growing line of Sandwich Company

products.

The

Sandwich Company continued to grow in size throughout the Golden Age of

American agriculture (1865-1920) with only a few dips. In 1904, the

Company reported gross sales of $925,994.59. However, in 1907, there was a

dip in gross sales to $736,490.78 caused by the contraction of the money supply

in October of that year which has been called the Panic of 1907. (George

E. Mowry, The Era of Theodore Roosevelt [Harper Bros.: N.Y. 1958], p.

217.) Still, in 1907, the Sandwich Company employed more than 250

people. In 1908, gross sales returned and were in excess of

$819,500.00.

Meanwhile,

a very efficient sales network had been established by the Sandwich

Company with branch offices in Council Bluffs, Iowa; Cedar Rapids, Iowa;

Peoria, Illinois; Bloomington, Illinois; and Kansas City, Missouri, all of which

had rail connections to the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy

Railroad. Warehouses for storing its machinery were established

across the country at strategic locations such as Sioux City, Iowa; Cedar

Rapids, Iowa; Jackson, Michigan; Denver, Colorado; Portland, Oregon; and Los

Angeles, California. Additionally, Sandwich began selling farm

machinery to South Wales, Canada, South Africa, Australia, Central and South

America, and especially to the Republic of Argentina after J. Phelps Adams made

several trips there to develop contacts. Locally, Illinois farmers could

buy Sandwich equipment from dealers in Somonauk, Shabbona, Hinckley,

Big Rock, Aurora, Yorkville, Waterman, Earlville, and DeKalb. Similar

dealership networks existed in other states, making the various Sandwich

Company farm machines available to farm customers across the midwest.

One of these customers was John Marshall Hanks and his son Fred Marshall Hanks

of Winnebago, Minnesota.

Fred

Marshall Hanks farmed his parents’ (John Marshall and Charlotte Bruce Hanks)

farm in Verona Township, Faribault County near Winnebago, Minnesota. Fred

Marshall and his father were both born in Warren, Vermont. In 1880, John

Marshall brought his family to Minnesota. From 1880 until 1882, the family

rented the Hamelau farm directly adjacent to the District No. 5 Schoolhouse in

Verona Township. In 1882, they purchased a 160-acre farm one mile to the

south and about a half mile to the west of the Hamelau farm. In 1900, the

family had purchased the neighboring 40-acre Baldwin farm to add to their 160

acres.

Because

his father liked woodworking (and indeed was a master woodworker) and was busy

putting his skills to work in a profitable way by building barns in the

surrounding neighborhood, much of the farming operation fell to Fred

Marshall. However, Fred Marshall really loved farming and had many ideas

for improvements. One such improvement was to shorten the labor-intensive

job of putting up hay for the livestock each year. Like most farmers with

dairy operations, the Hanks family had to store a great deal of hay to feed the

cattle in winter. Hay-making was a big job which took days, and even

weeks, to perform under the hot summer sun. Of course, mowing the hay was

done with a horse-drawn mower and the hay dried in a swathe. Gathering the

hay into bunches in the field could be accomplished by use of a team of horses

and a dump rake. (The dump rake used by the Hanks family is still located

on the Harlan Hanks farm in rural Winnebago, Minnesota.) Loading of the

hay was, however, accomplished entirely by hand.

In late

June of 1911, with the sweet smell of freshly mown hay in the air (the mowing

had been accomplished the day before), Fred and his sons, 15-year-old Howard and

8-year-old Stanley, headed to the hay field with pitchfork in hand, a team of

horses, and a hayrack. The morning milking was done and the dew had

lifted. Grandfather John Marshall was already in the field with another

team of horses, pulling the hay together in piles with the dump rake. Once

in the field, young Stanley, driving a team of horses, moved the hayrack from

one pile of hay to the next as his older brother, father, and grandfather loaded

the hayrack full of hay. One fork-full at a time, the entire hay crop

would be loaded onto successive wagons and hauled to the barn. It was a

tedious, time-consuming job which could last for days, two or three times a

year, as the first, second, and third cuttings of hay were harvested.

Therefore, it is easy to understand the intense desire of Fred Marshall to find

an easier way to put up the hay crop.

After

pondering the question all winter, Fred went to Winneabago in the spring of 1912

and ordered a “Clean Sweep” hay loader made by the Sandwich Company and

a Keystone side-delivery rake. That summer, the new

Sandwich hay loader was put to use on the Hanks farm and considerably

shortened the hay season. (A more detailed description of the

Sandwich hay loader on the Hanks farm during the 1919 hay harvest is

contained in the article “The Larson Bundle Wagon” on page 28 of the March

/April 1996 Belt Pulley, Vol. 9, No. 2.)

There were

two major shortcomings to the Sandwich Clean Sweep hay loader: first,

it was made largely of wood; and second, it was extremely tall. Indeed,

the tall, awkward nature of any model hay loader meant that it was destined to

be stored outside all winter long. This meant that the weather would have

a very real deleterious effect on the hay loader, especially its wooden parts,

and like most farms, indoor storage space was at a premium on the Hanks

farm. Consequently, by 1920, the badly deteriorated wooden

Sandwich hayloader had to be replaced by a brand new John

Deere-Dain direct-drive, all-steel hay loader.

Another

drawback to the Sandwich hay loader was that it required the use of

three horses to pull the wagon and the hay loader. The Clean Sweep’s

wooden frame pickup cylinder was heavy and created a heavy draft. By

comparison, the new John Deere-Dain hay loader purchased by the Hanks

family in 1920 had a lighter-weight pickup cylinder made of metal which

considerably lighten the draft and required only a two-horse hitch.

In the

pattern of the harvest season on typical midwestern farms, the hay harvest is

followed by the oat and wheat harvest. Between the years of 1911 and 1919,

the Hanks family hired their neighbor, Ray Iliff, to thresh their wheat and

oats. Here again, the Sandwich Manufacturing Company played a

role. In the evening of one summer day in 1911, a Minneapolis

steam engine came chugging down the road toward the Hanks farm with a 36?

x 58? Minneapolis thresher in tow. Ray Iliff had just

finished threshing at another farm and was bringing the thresher to the Hanks

farm where he would begin threshing the next morning. In the approaching

darkness, the groans and creaks of the steam engine, as well as the size of the

engine and thresher with its Garden City Company double-wing feeder

extensions, created a frightening specter in the mind of young 6-year-old

Harlan. He ran inside the house and stayed there, where he explained the

scary scene to his mother, “Nettie” (Jeanette Ogilvie Hanks). Only the

excitement of threshing the next day brought Harlan out of the house to view the

steam engine and thresher in the light of day. The new day brought another

Ray Iliff machine down the road. Horses pulled into the Hanks farm yard

with the Sandwich portable grain elevator. Accompanying the

elevator was a hit and miss Sandwich engine dressed in its rich

Brewster green paint striped in gold and light green.

Even

though the Sandwich elevator was portable, it took a lot of work to set

it up at each farm. Indeed, young Harlan Hanks remembered that the

Sandwich elevator was only used one year on the Hanks farm because it

was regarded as too much bother to set it up for the amount of time it might

save. The men setting up the portable elevator barely had enough time to

get the stationary “hit and miss” engine started and the elevator operating

before the first wooden “double box” wagon load of grain would come into the

yard.

With the

arrival of the Sandwich hay loader on the farm and now this new

motorized method of lifting grain into the granary by means of a

Sandwich elevator, Howard must have thought modern farming had truly

arrived on the farm. Thus, he got his new camera and snapped a

picture. Such a sight was surely worthy of being preserved on film.

Forty-seven years later, Howard’s grandson, the current author, would also take

a picture of a grain elevator in operation on his home farm loading oats into a

grain bin. At 9 years of age, this would be one of the author’s first

photographs. (Incidentally, this picture is carried in an article on page

30 of the November/December 1993 issue of Belt Pulley, Vol. 6,

No.6.)

Howard was

right. Modern farming had arrived on the Hanks farm in 1912.

The Sandwich Manufacturing Company had been responsible for

bringing modern operations to the Hanks farm just as it had to many other

farms. The Sandwich Company continued to grow on the basis of its

innovative machines and farmers’ demands for modern Sandwich Company

farm equipment products. At its peak, the Company would employ 400

persons. As the agricultural market began to shrink following World War I,

however, the United States rural economy began to enter its depression in

1921. The Sandwich Company, like other farm equipment companies,

found itself in a bind. Things progressively went from bad to worse for

the Sandwich Company, as the agricultural depression of the 1920

deepened and spread into the industrial sector following the 1929 stock market

crash. However, in 1930, the Sandwich Manufacturing Company was

sold to the New Idea Spreader Company of Coldwater, Ohio. New

Idea continued to sell Sandwich corn shellers, hay mowers, side

rakes, portable grain elevators, and, of course, the famous “Easyway” hayloader

under the New Idea Company name. In 1945, AVCO

would buy out the New Idea Company. Manufacture of the hay loader

would cease altogether some time between 1949 and 1952, as more and more farmers

began baling their hay.

The old

plant in Sandwich would continue to manufacture farm machinery, including

mowers, side rakes and elevators, until 1955, when the antiquated little factory

in Sandwich would be closed down permanently. Although the facilities

would continue for a time as a sales division and warehouse for machine parts

manufactured by the New Idea Division of AVCO, the town of

Sandwich realized that it had lost its primary employer, and the city mourned

that loss.

Today, the

community of Sandwich still fondly remembers the farm equipment company.

Today, Sandwich has its own historical society which has collected much material

on the Sandwich Company. Sandwich resident, Roger Peterson, has

collected a number of antique Sandwich Company gas engines as a

hobby. Perhaps in the near future, a club of collectors and restorers will

spring up which will make some of the old Sandwich Company’s machines

come alive again for the public to enjoy. This would be a fitting tribute

to the small company that was a pioneer in so many areas of American

agriculture.

more