Prison-Made Steam Engines: The Northwest Thresher Company Began with Minnesota Prison Labor

The Giant and New Giant steam traction engines – among the most noteworthy steam engines built in Minnesota – pack a few surprises.

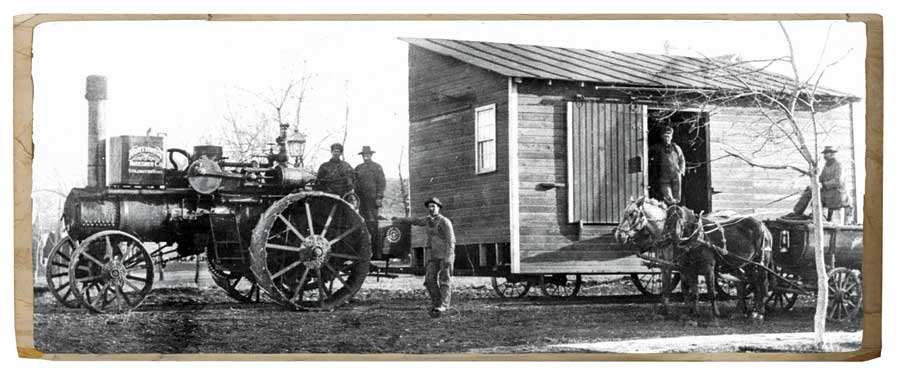

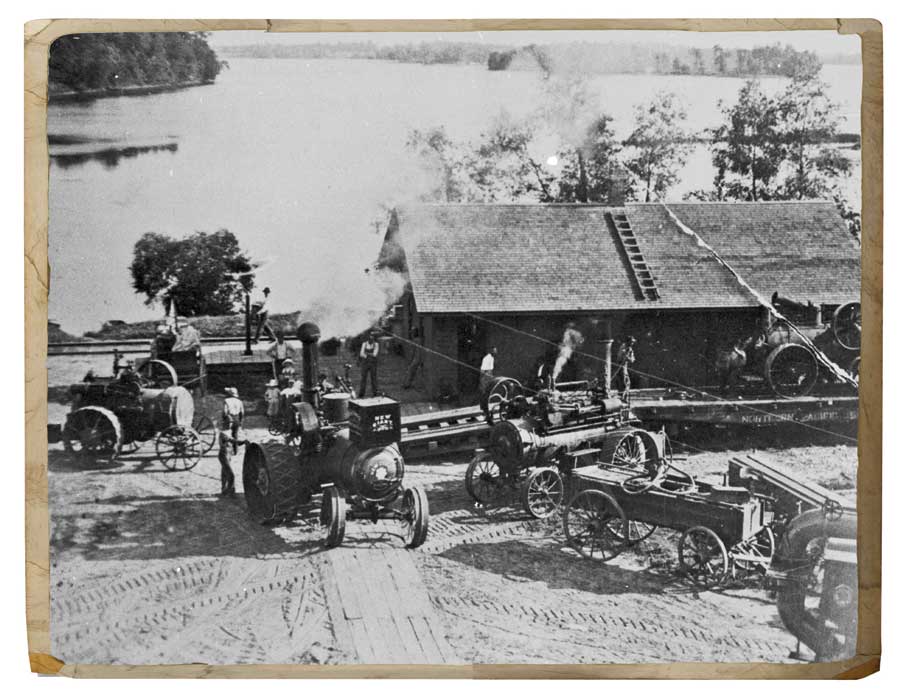

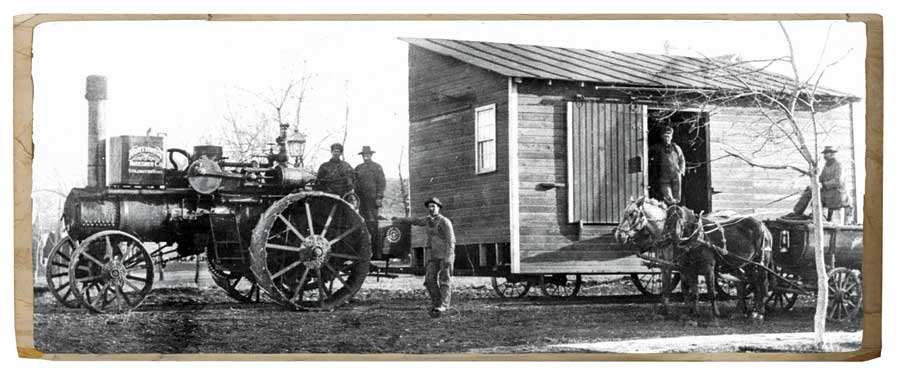

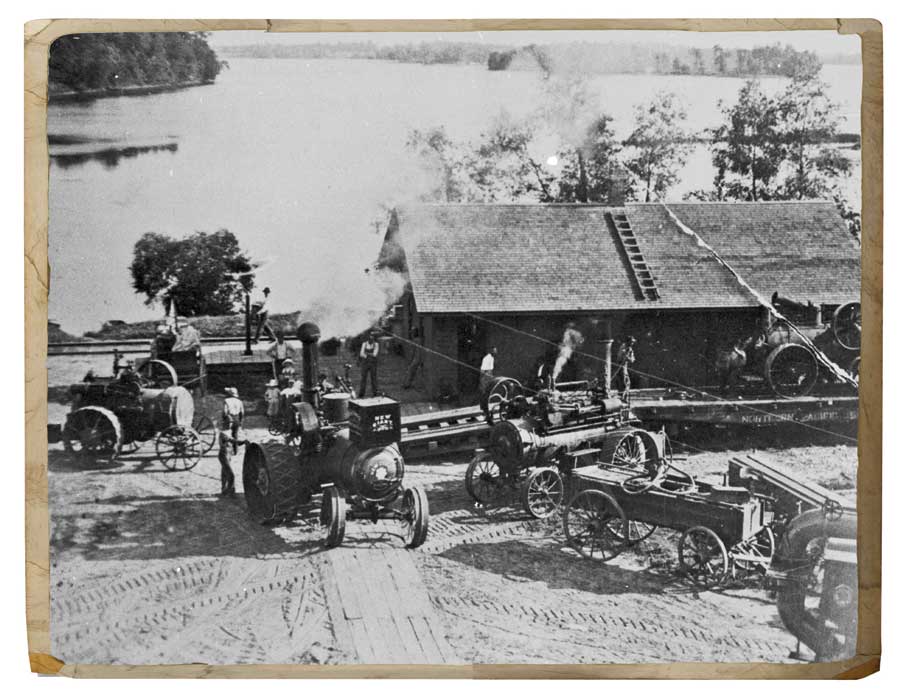

Early entrants to the industry, the steam engines were built almost as a sideline by an established manufacturer of threshing equipment. And then there’s the way they were built. Visitors to a Stillwater, Minn., “manufactory” where steam engines and threshers were built during the 1880s had to be surprised, if not shocked, by what they saw.

“Here are horse thieves,” reported a writer in the Independent Farmer and Fireside Companion, “petty thieves, forgers, defaulters and murderers, some of whom were once lawyers, doctors, merchants, farmers and mechanics, all filing, fitting, cutting and hammering at the various parts that go to make up the perfect machine. As you go through one room, blue-eyed Bob Younger looks up from his work, and Cole gives you a look like a startled wolf, while Jim hangs his head sullenly. They are busily engaged, doing excellent work,” for what would become Northwest Thresher Co.

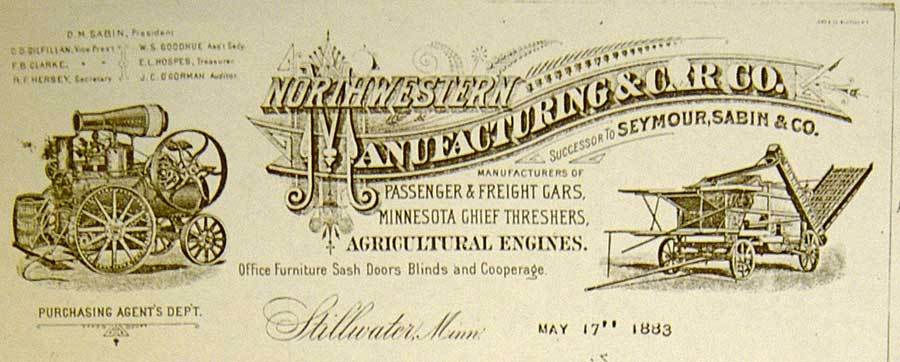

Back to the beginning: Seymour, Sabin & Co.

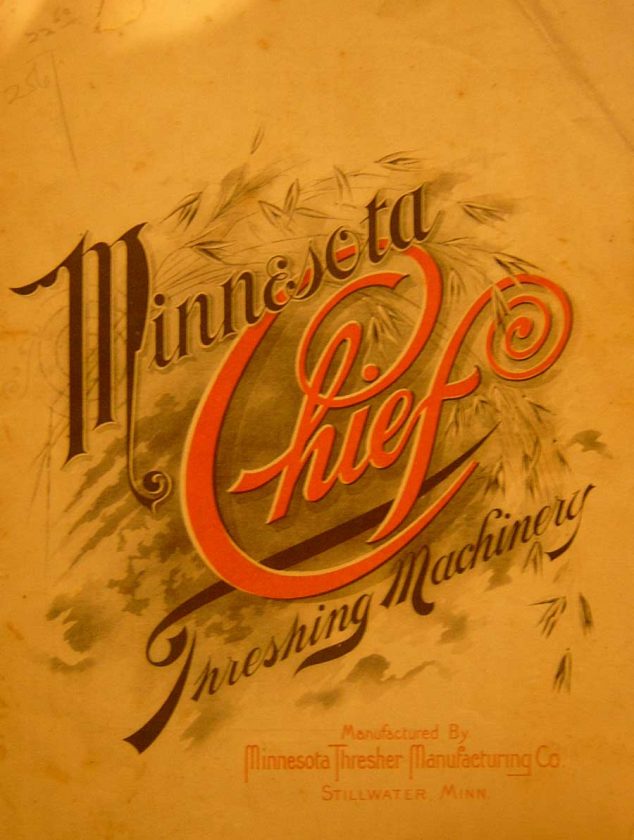

The earliest forerunner of Northwest Thresher Co. was Seymour, Sabin & Co., manufacturer of agricultural implements, which first contracted for prison labor in 1866 through the influence of U.S. Senator Dwight M. Sabin. An 1879 article in the Independent Farmer noted the need for solid technology: Farmers’ profits depended on getting every kernel of grain. “A thresher must be built that would do all this. But it takes capital to build such machines; capital composed of brains and energy as well as money to carry out and manufacture that invention produced; and this is why the Minnesota Chief (thresher) became a success as a specialty of Seymour, Sabin & Co.”

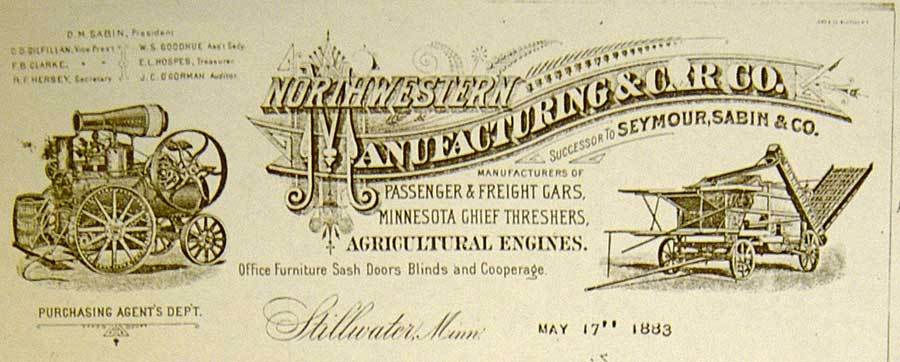

At about the same time, the company’s name was changed to Northwestern Mfg. & Car Co., possibly to launch a fresh start, as in the previous year the company recorded sale of only “one engine, zero separators and one horse power.” A product line expanded to include railroad cars may have been a last-ditch effort to stay afloat.

If so, the gamble worked. In 1884, manufacturing output jumped to 170 machinery items sold, including Minnesota Chief threshers and Minnesota Giant “straw-burning engines.” Things seemed to be looking up.

Still, the company struggled. Later that year, stockholders were informed of reorganization plans. Going forward, Minnesota Thresher Mfg. Co. would produce steam traction engines, horse powers and separators. Railroad boxcars were omitted from the plan (although two years later, in 1886, the company still advertised passenger, caboose and freight cars for sale). Most early investors reinvested in the new firm.

Minnesota Thresher Mfg. Co. and Minnesota Thresher Co. one and the same

The casual observer could be forgiven for thinking that there were now two different Minnesota Thresher companies operating out of Stillwater: one called Minnesota Thresher Mfg. Co., and the other, Minnesota Thresher Co. Apparently it was easier to say – and write – three words instead of four when identifying the company.

The 1884 company report stated the reorganization name of Minnesota Thresher Mfg. Co., and that was certainly the company’s official name. However, contemporary magazine tractors at times referred to it as Minnesota Thresher Co., as Farm Implements & Hardware did in its February 1889 issue: “The Minnesota Thresher Co. sustained,” reads the headline. During the next year, tractors appearing in other issues also referred to the firm as Minnesota Thresher Co.

Built by prison labor

The August 1888 issue of Farm Implements gives insight into the use of prison labor in the era, saying, “The Minnesota Thresher Mfg. Co. shows for the work done during 1888, 900 machines and 450 engines. The labor of the convicts has not been an unmixed blessing to the company and as the contract of the company with the state expires Sept. 1, we may expect to see the next season one of greater farm activity outside the walls of the prison than this last one has been inside those same walls. The company will utilize several large buildings (on its own Stillwater site) for machine shops that have heretofore been used for storage.”

The relationship was an uneasy one. Minnesota State Prison Warden J.A. Reed wrote that the buildings erected by Minnesota Thresher “are unsightly and occupy a large amount of space much needed for other uses. The contractors have also declined to pay the rent for the use of the prison ground.” The company retorted that it would not pay the money until the “terms of the contract” were met, which included posting two additional “trusty and vigilant guards,” as well as keeping one particular prisoner away from the work altogether.

Ultimately, Minnesota Thresher must have won a lucrative agreement. In November 1889, Farm Implements reported, “The Minnesota Thresher Co. has made a contract whereby a portion of the convict labor at Stillwater will be employed by them. The stone building used as a machine shop has been torn down and a new building is being erected in its stead, which will be 12 feet wider than the original one.”

Prison labor appears to have been used for the next eight years, as in December 1897 Farm Implements announced, “The Minnesota Thresher Mfg. Co. of Stillwater, Minn., has begun the erection of a foundry and machine shop adjoining its large iron-clad warehouse in that city. The machinery owned by this company and formerly operated in the prison shops is being overhauled and will be set up for operation in their new quarters.”

“Perfection attained” with the Minnesota Chief separator

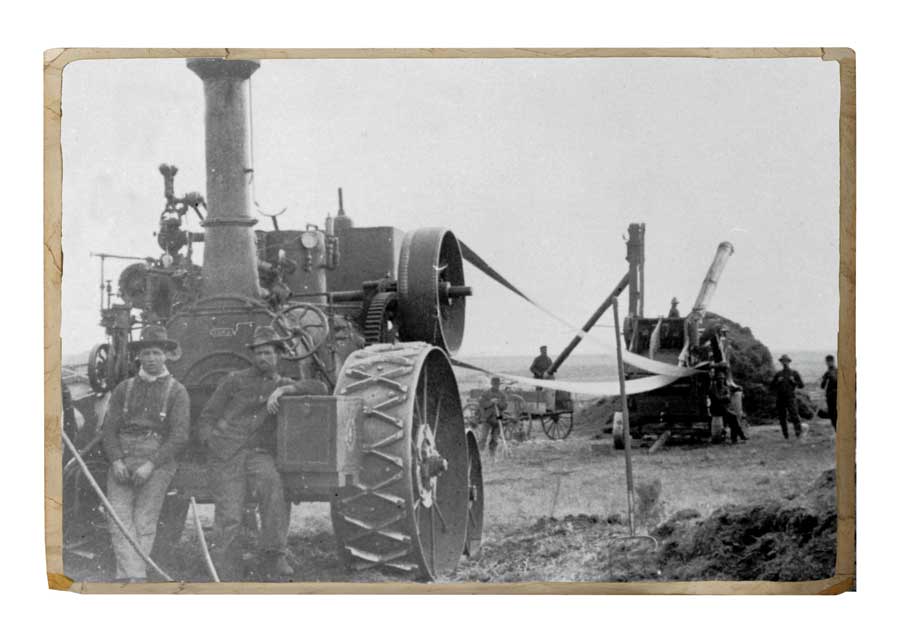

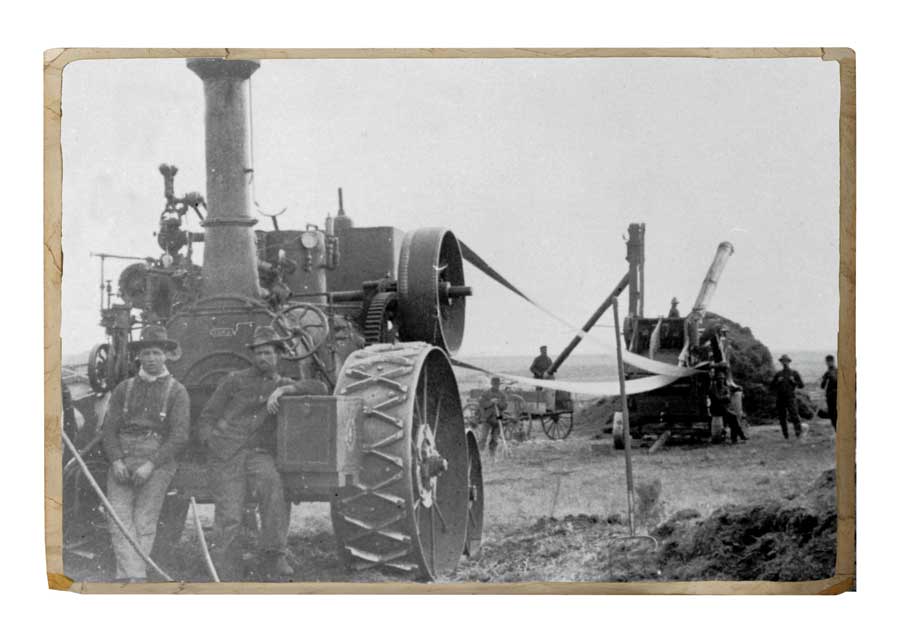

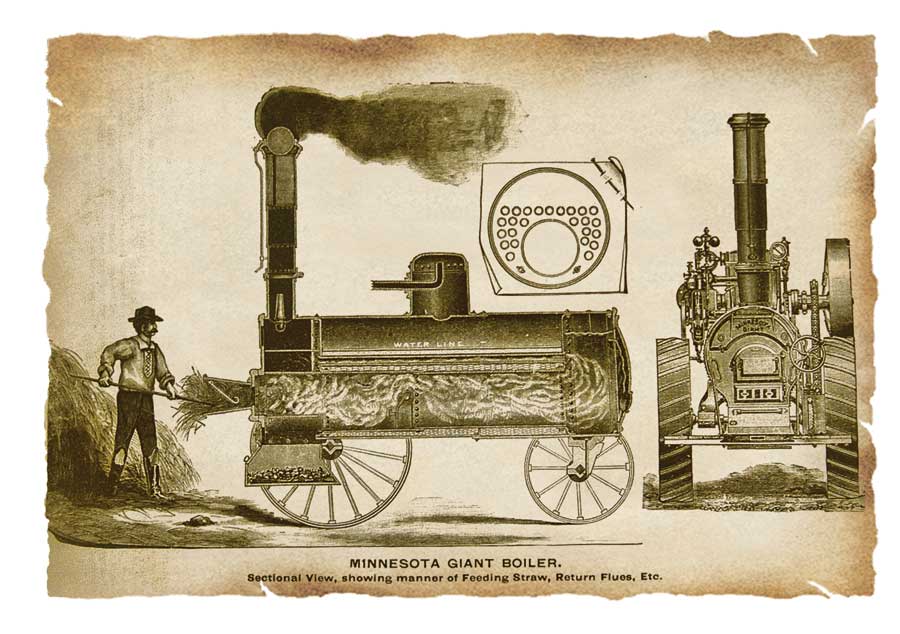

By 1898, Minnesota Giant self-steering traction engines were sold throughout the U.S. at prices ranging from $1,350 (about $34,000 in today’s terms) for the 12 hp engine to $1,700 (about $43,000 today) for the 18 hp model. In an 1898 stockholders’ report, the Giant is touted as having almost-equal distribution of weight on the four wheels, “removing the danger of tipping up when ascending hills, and obviating the necessity of loading it down with a large water tank at the front of the boiler, and what is still more unpleasant to an operator, going up a hill backward.”

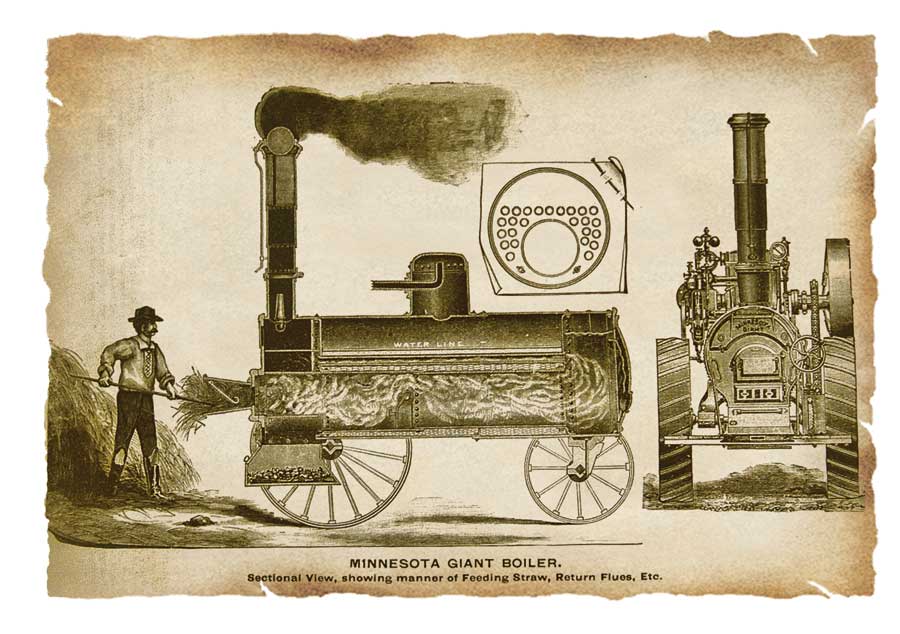

The report also boasted of the design of another product, the Stillwater engine: “The engine’s return flue, being placed above the lines of the crown sheet, ensures a depth of several inches of water over it, so that it is never exposed in ascending or descending hills, and this, with the arch-like shape of the crown sheet, makes it so strong and safe that not a single instance of collapse or sagging of the crown-sheet has occurred in any one of the many hundreds of these boilers that have been and are now in use.”

According to information in Iron-Men Album (later, Steam Traction) archives, the Giant was built with a cylindrical (or tube-type) boiler. It was a return-flue engine, built something like the return-flue Minneapolis or Avery, which came later. The other engine, the Stillwater, was built with a fire-box boiler. The Giant would burn straw, wood or coal.

Mounted on these different boilers, the engines were otherwise identical. They were equipped with a Gardner governor, reverse, friction clutch and drum brake. Water was supplied to the boilers by the Clark independent pump, which was a small steam engine with a built-in pump. Both engines were equipped with a chain traction of flat link, malleable iron chain, and each was available in either portable or traction configurations. Both were initially mounted on wooden wheels, but steel wheels soon replaced the wooden ones.

Minnesota Thresher also launched a new – or at least partially new – separator in 1898. “The cylinder of the Northwest is substantially the same as in the Minnesota Chief separator,” noted the stockholders’ report. “Experience has taught us that the cylinder in the Chief is perfect, and perfection having been attained, we simply let well enough alone.” The report added that the separator “gave such excellent satisfaction that we found a ready sale at a reasonable profit for all that we were able to manufacture.”

Meanwhile, Senator Sabin continued to see a market for railroad cars. “A plan is on foot for the thresher company at Stillwater to lease some of their buildings at that place,” reported an article in a November 1889 issue of Farm Implements, “and take stock with eastern capitalists in a company Senator Sabin is organizing to build cars at Stillwater.” Apparently nothing came of that effort.

Becoming Northwest Thresher Co.

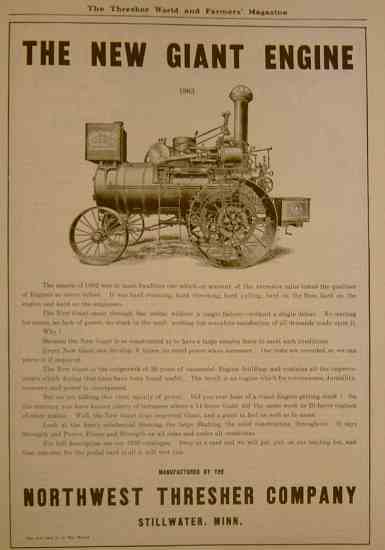

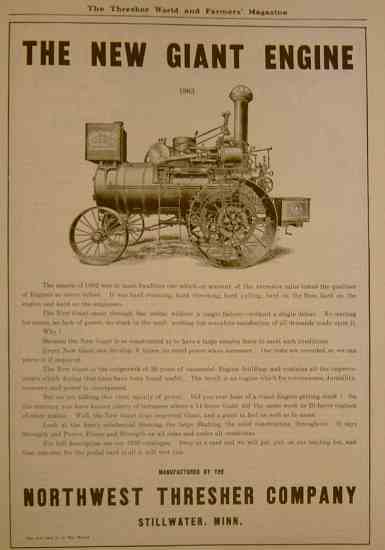

Northwest Thresher Co. became the successor to Minnesota Thresher Mfg. Co. in July 1901. A larger plant was built to produce a new product line, including, as a 1903 ad in The Thresher World and Farmers’ Magazine announced, the New Giant engine, successor to the Giant steam traction engine. The ad acknowledged that excessive rain in 1902 administered a brutal test. “It was hard steaming, hard threshing, hard pulling, hard on the flues, hard on the engine and hard on the engineers,” the text read. “The New Giant came through the ordeal without a single failure, without a single defeat. No waiting for steam, no lack of power, no stuck in the mud; nothing but complete satisfaction of all demands made upon it.”

The New Giant was claimed to be the most durable boiler on the market, with 60,000-pound tensile strength per square inch. Shells on 18 hp and smaller boilers were 1/4 inch thick, 20 hp and larger were 5/16 inch thick, and 25 simple and 30 hp compound boilers were 13/32 inch thick in the middle and 3/8 inch thick on both ends.

In Encyclopedia of American Steam Traction Engines, Jack Norbeck wrote, “The company made no extra charge for jacketing. The jacket of the New Giant had an extra covering of Russia iron, which made it indestructible and gave it a fine finish. This prevented the condensation of steam in cold weather, and added to the durability of the boiler.”

A forward-thinking enterprise, Northwest Thresher required each of its boilers to be state-tested. The company was fully committed to the integrity of the process in the name of public safety. “It won’t make one cent’s difference with me who is appointed (steam boiler inspector) beyond the desire to get the best man,” declared a company representative in 1905. “The place, the property and even the lives of citizens is involved in this matter, and to this extent it should be every good citizen’s privilege, and aim, to do what little he can toward the desired end.”

Northwest Thresher engines were steamed up for four consecutive days while the boiler inspector checked them. They were run at 50 percent above their steam test. Thus the New Giant, which carried 150 pounds of steam, was tested at 225 pounds of cold water pressure.

Bought out by M. Rumely Co.

Even as steam traction engines continued to be manufactured and widely used, their days were numbered. In early 1911 Northwest bought Universal Tractor Co. of Stillwater, “and the business will be carried on hereafter under the name of the Northwest Thresher Co.,” reported an article in the Feb. 28, 1911, edition of Farm Implements, “which will continue to manufacture threshing engines and separators but in addition will make the gasoline traction engine heretofore made by the tractor company.”

One year later, according to an article in Farm Implement News, “eastern interests” bought Northwest Thresher Co., and announced plans to increase production. From a 1912 article in Farm Implements: “A dispatch from Stillwater says the Northwest Thresher Co. is rushing the construction of gasoline tractors to fill big orders, and at the same time is turning out the usual quota of steam tractors and thresher separators. Many tractors were for Minneapolis Threshing Machine Co., then Rumely Products Co., Ltd., LaPorte, Ind. A train of 17 cars left the factory March 13.”

New machinery was added, the plant was enlarged, and in October 1912, Northwest Thresher Co. was sold to M. Rumely Co., LaPorte. A year later, perhaps due to competitive pressures, the plant was shut down and Northwest Thresher Co. was finished. FC

For more on prison labor in Minnesota, see Let’s Talk Rusty Iron, Farm Collector, April 2008.

Bill Vossler is a freelance writer and author of several books on antique farm tractors and toys. Contact him at Box 372, 400 Caroline Ln., Rockville, MN 56369; e-mail:bvossler@juno.com.